Part of the joy of Advent lies in celebrating the birth of Christ through literature, fine art, and music. Biola University leads the way each year, with a project uniting those three disciplines with biblical analysis and reflection.

Biola’s Advent devotional is a feast for the senses. The daily experience is rooted in the goals of classical-Christian education—a pursuit of the good, the true, and the beautiful. One of the artists Biola featured this past Christmas was Malcolm Guite, a Cambridge, England-based poet, author, Anglican priest, teacher, and singer-songwriter. Their reference to Guite spurred me to explore his website, which is filled with thought-provoking work.

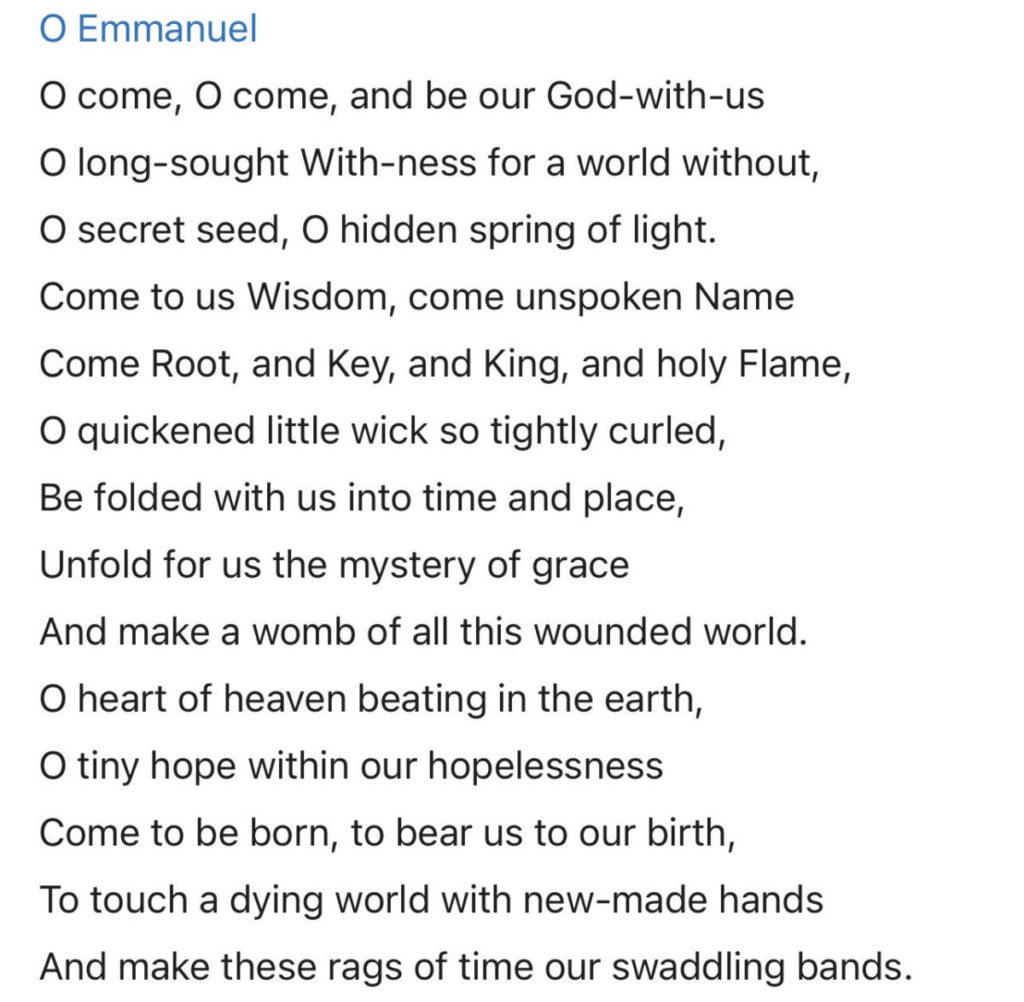

His poem, “O Emmanuel,” reminds readers that though the birth of Christ is a mystery, its message is clear: the baby brings “tiny hope.” Tiny, but mighty enough to carve his way through our vast “hopelessness”:

If Guite paints a poignant picture of Christ’s birth with words, the Dutch painter Gerrit Van Honthorst does the same with brush strokes. His Adoration of the Child (1619-1620, oil on canvas, The Uffizi) is haunting in all the right ways.

Reminiscent of Caravaggio’s masterful use of light and dark (chiaroscuro), the painting illuminates the faces of the three figures peering over the baby—Mary, and two angels. Joseph floats in the shadows behind Mary. The angels’ golden gazes are matched by Mary’s knowing countenance:

A Dickensian View of Christmas

Another master of Christmas reflection is Charles Dickens. His Christmas Carol, a divine ghost tale, is featured in Hillsdale College’s newest online course, led by professor Dwight Lindley.

Lindley’s insights and analyses challenge students to think deeply about the novella’s core themes: change and conversion; divine encounters among the poorest people, and the smallest aspects of life; and the power of memory.

The ghosts of Christmas past, present, and future permanently alter Scrooge. “He learned to fill up his time with love, and to live life as a loving response to the call of creation, and of everything that he sees,” Lindley explains.

Readers witness the full conversion of a miserly wretch into Scrooge 2.0: “We’re seeing a man … who has rediscovered his own childhood, who is child-like himself in an important, deep, healthy way. This is a new birth. This is somebody who has been rejuvenated by the mystery of the incarnation,” Lindley says. “A big part of the mystery of this book is encountering the divine, and in that encounter, becoming a child yourself. There’s a reciprocity there.”

Many institutions in the west have devalued great works like those written by Dickens. It’s to the detriment of our children’s imaginations, creativity, and critical thinking. Perhaps Lindley’s most valuable analysis is delivered when he explains why it’s important to read the classics.

“Great, imaginative literature teaches us anew how to see old things—the stuff of the world that we tend to pass by and see without insight or wonder. Those things all can be awakened by a great work,” Lindley says.

Cinematic interpretations of A Christmas Carol, for instance, have their place, but they cannot deliver the depth that comes with reading words on a page. Lindley’s lectures delve into those words, and the suggestions and allusions they inspire. The course is a deep dive into “the world of suggestions, which is a big part of the world of A Christmas Carol.”

These are just a few of the gems offered in the course, which runs a little over three hours, across six different lectures.

Leave a Reply