Twenty-two years ago, New York City firefighters climbed the stairwells of the Twin Towers, clad in heavy gear, knowing they might not leave the burning buildings alive. Documentaries and news reports about 9/11 have cited survivors who passed the ascending firefighters: They moved into the smoke and the flames without hesitation. They didn’t flinch as they rushed to rescue people.

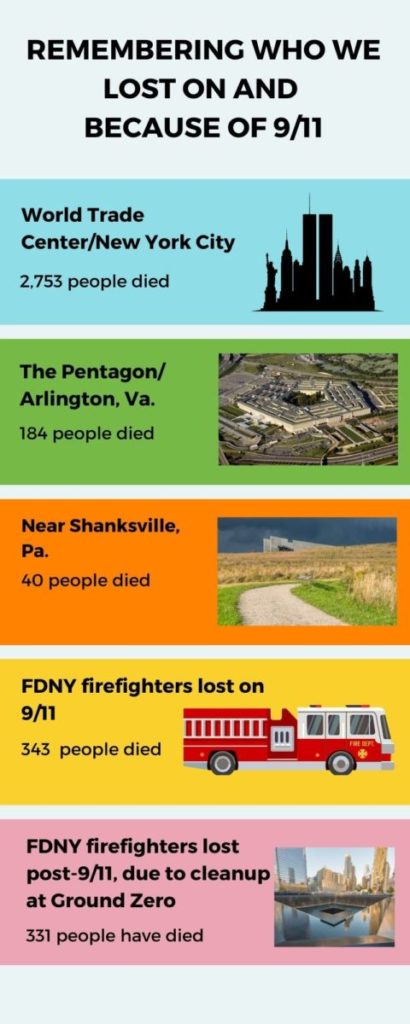

The death toll amounted to 2,977 people in New York, Arlington, Va., and Shanksville, Pa. (not including the terrorists). It marked the largest-ever loss of life on U.S. soil due to a terrorist attack. Among the dead were 343 from the Fire Department of New York, 23 NYPD police officers, and 37 Port Authority police officers, according to the 9/11 Commission.

The Port Authority’s losses were the most for any police force in history. Since 9/11, another 331 FDNY firefighters have died from illnesses related to their cleanup efforts at and around Ground Zero.

Just 19 men carried out the attacks, most hailing from Saudi Arabia. They hijacked four commercial jets and slammed them into the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center, the Pentagon, and a Pennsylvania field.

The Twin Towers were one-third to one-half occupied when the planes hit, according to a report by the National Institute of Standards and Technology. If they had been fully occupied—with 20,000 people in each—about 14,000 may have died. The stairwells didn’t have the capacity to evacuate that many people in the time between the planes striking and the towers collapsing.

In the days and weeks immediately after the attacks, Americans were unified with the same mindset: we would overcome the evil meant to pull us apart. Ours was a country worth defending and preserving. It was the silver lining to one of our darkest days, and an important legacy. More than two decades later, other legacies have taken shape–some vital to the country’s future, while others are proving detrimental.

The War on Terror

The late Osama bin Laden, former head of al-Qaeda, is credited with devising the attacks, while Khalid Sheikh Mohammed was in charge of operations. Mohamed Atta, one of the 19 hijackers, was the ringleader. He flew American Airlines flight 11 into the north tower of the Trade Center.

Atta and Marwan al-Shehhi, who flew United Airlines flight 175 into the south tower, took flying lessons at a Florida aviation school. There they applied to change their visa statuses, from tourists to students. They ostensibly sought student visas to comply with U.S. immigration regulations.

As investigators pieced together the hijackers’ identities, backgrounds, and motives, President Bush called for a war on terror. He addressed the country and a joint session of Congress on September 20, 2001, saying:

The enemy of America is not our many Muslim friends. It is not our many Arab friends. Our enemy is a radical network of terrorists and every government that supports them.

Our war on terror begins with Al Qaeda, but it does not end there. It will not end until every terrorist group of global reach has been found, stopped and defeated.

Americans are asking “Why do they hate us?”

They hate what they see right here in this chamber: a democratically elected government. Their leaders are self-appointed. They hate our freedoms: our freedom of religion, our freedom of speech, our freedom to vote and assemble and disagree with each other.

They want to overthrow existing governments in many Muslim countries such as Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Jordan. They want to drive Israel out of the Middle East. They want to drive Christians and Jews out of vast regions of Asia and Africa.

The war on terror reverberated at home and abroad. Not long after Bush’s speech, America and its allies launched a war in Afghanistan, aimed at routing al-Qaeda and stretching through 2014. By 2003, America had invaded Iraq, an operation that lasted until 2010.

On March 11, 2002—exactly six months after 9/11—the former Immigration and Naturalization Service informed the flight school that Atta and al-Shehhi’s student visas had been approved. The grave misstep drew the ire of government and education officials. They deemed it proof of the dire need to reform the INS and the student-visa system. The Homeland Security Act of 2002 dismantled the INS and rolled its functions into three agencies within the new Department of Homeland Security.

American forces killed bin Laden in 2011. Sheikh Mohammed, who was captured in 2003, has been on trial for more than a decade, along with four co-defendants. In August, news broke that the Pentagon had sent a letter to families of some who died on 9/11, explaining that Sheikh Mohammed and his co-defendants might not face the death penalty.

The prosecution is considering plea agreements that could “remove the possibility of the death penalty,” according to the Associated Press. The move has rightly infuriated 9/11 families. According to the AP report, “It’s about ‘holding people responsible, and they’re taking that away with this plea,’ said Peter Brady, whose father was killed in the attack. … The case ‘needs to go through the legal process,’ not be settled in a plea deal, Brady said.”

A Legacy Distorted

Beyond the war on terror, and in a sad, ironic twist, part of September 11’s legacy lies in the expansion of an American police state. Journalists and thought leaders have reported on this.

Investigative reporter Matt Taibbi said that America’s policy response to 9/11 has spurred a permanent emergency mindset. Shortly after the attacks, U.S. lawmakers passed the Patriot Act and created the Department of Homeland Security. The Patriot Act launched “a long period of radical change,” Taibbi said. Meanwhile, the Bush administration hatched the DHS to manage national security, meeting resistance from Democrats.

Investigative reporter Lee Fang reported that Democratic opposition was led by Wisconsin Senator Russ Feingold. Feingold said DHS was developed “at the expense of unnecessarily undermining our privacy rights” and “weakening protections against unwarranted government intrusion into the lives of ordinary Americans.”

Fang highlighted thoughts from Chris Bell, a Democratic representative from Texas, who “fumed at the agency and warned against the creation of an ‘Orwellian surveillance state’ that would be used to settle ‘partisan political’ disputes.”

In the meantime, DHS has ballooned. It boasts more than 260,000 employees around the world and a $103 billion budget—up from $46 billion in 2003.

When Trump sailed into the political fray, Democrats recast their views. They’re now strong advocates for DHS. Along with other elites and mainstream media, they believed Trump was elected because Russia used social media to help him. Their argument, often dubbed “Russiagate,” was widely discredited.

The Columbia Journalism Review released a four-part series in January examining the press, Russia, and Trump. Former New York Times reporter Jeff Gerth wrote the piece, interviewing Trump and his enemies, including Christopher Steele and Peter Strzok. “I also sought interviews, often unsuccessfully, with scores of journalists—print, broadcast, and online—hoping they would cooperate with the same scrutiny they applied to Trump,” according to Gerth.

He went on to note: “On the eve of a new era of intense political coverage, this is a look back at what the press got right, and what it got wrong, about the man who once again wants to be president. So far, few news organizations have reckoned seriously with what transpired between the press and the presidency during this period. That failure will almost certainly shape the coverage of what lies ahead.”

Ashley Rindsberg wrote in The Spectator that “The CJR piece represents a turning point not just for Russiagate but for the American media. In fact, one of the many effects of the piece will be to redefine Russigate itself from a series of questionable interactions between Trump and the Kremlin to a protracted media effort to remove a sitting president from power. In the words of former Wall Street Journal editor-in-chief Gerald Baker, reported in Gerth’s CJR piece, Russiagate was ‘among the most disturbing, dishonest, and tendentious [media episodes] I’ve ever seen.’”

Meanwhile, Fang reported that of the $100,000 Russia invested in political ads online, a significant amount bolstered left- and right-wing groups. Little was directed to support Trump. “For perspective, that amount of Russian online disinformation advertising was 0.001538% of the $6.5 billion spent that year, the equivalent of a drop of water in a vast political swamp,” Fang said.

Still, Russiagate wielded tremendous power—enough to spark changes at DHS. According to Fang, “the Obama administration designated ‘election infrastructure’ as a critical form of infrastructure under the purview of the agency, alongside pipelines, utilities, chemical plants, and other forms of traditional infrastructure, setting the stage for DHS to begin formulating its censorship apparatus.”

Since that designation, DHS has collaborated with Facebook, Google, and X (formerly Twitter) “to discourage supposed misinformation, disinformation, and ‘malinformation.’”

Censorship and the American Police State

Dr. Robert Malone referenced these terms in a recent episode of American Thought Leaders Now, addressing the government’s push to censor information that could cause people to doubt or question the Covid-19 vaccines.

“We have these three key words that have been injected into our lexicon: mis-, dis-, and malinformation,” Malone said. “They were really crystallized in a statement that came from Secretary Mayorkas and the Department of Homeland Security that defined those that would spread mis-, dis-, and malinformation as domestic terrorists.”

The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency’s website explains the terms this way:

- misinformation is false, but doesn’t cause harm;

- disinformation intentionally misleads, harms, or manipulates people, social groups, organizations, or countries; and

- malinformation is fact-based “but used out of context to mislead, harm, or manipulate.”

Malinformation, Malone said, is “fascinating.” While true, he said, it’s defined as information that would prompt audiences “to become critical or question the authority or the policies of the United States government.”

Talk-radio host and podcaster Dan Bongino said during his September 11 podcast that it’s “a day to remember, and a day to throw the caution flag.” The 9/11 terrorists attacked the American system of freedom and liberty. In remembrance of those who died, we should preserve that system, Bongino argued. Yet, Americans have surrendered their freedom and liberty, and the Patriot Act marked the beginning of that unraveling.

Bongino, who was a federal agent in New York on 9/11, investigated the terrorists and their networks. He witnessed how lawmakers used the emergency of September 11 as an excuse to work around the Constitution. He eventually ran for office, campaigning against the Patriot Act. Bongino worried the law eventually would be used more broadly to implement a police state.

“We cannot use a national emergency as an excuse to scrap the Constitution. The Constitution was precisely written for national emergencies when people would use an excuse to try to forfeit the Constitution, which was never meant to be a suggestion. Everything we’ve warned you about—it is happening right now,” Bongino said.

A national survey conducted in mid-September found that more than two-thirds of U.S. voters are worried the country is becoming a police state. Rasmussen Reports, which led the telephone and online poll, defines a police state as “a tyrannical government that engages in mass surveillance, censorship, ideological indoctrination, and targeting of political opponents.”

More specifically, 72 percent of likely voters are concerned that America is morphing into a police state, and 46 percent are very concerned. Just 23 percent are not concerned.

An Irresponsible Press=An Unfree America

I lived and worked in the D.C. area on 9/11. It’s impossible to overstate the enormity of that day and its aftershocks. I covered the impact on higher-education policies, including student-visa reform and international education. As with the Patriot Act, some equated the higher-ed policies with government overreach.

Back then, I wrote news and features for a newspaper and withheld my opinions. My purpose in this piece is different. These days, corporate media presents one side of the story—the side that makes far-left policies shine at all costs. They don’t do the most important part of their job: keeping public servants accountable to the people who elect (hire) them. Minus that accountability, politicians run amuck. Amuck they’ve gone, with our country in tow.

The Fourth Estate railroads Trump into what they hope is oblivion while covering for Biden’s glaring failures with the economy, the border, and his daily stumbles, both physically and verbally. If these so-called journalists were striving for objectivity and fairness, they would treat both men with scrutiny while giving credit where it’s due.

In 1947, The Commission on Freedom of the Press released a report that found the freedom of the press was in danger. As the press became “an instrument of mass communication,” it failed to meet society’s needs. The report is a mirror for our time, a prescient reminder of modern media’s lack of freedom—and the threat it poses to the American way of life.

According to the report, the press “can play up or down the news and its significance, foster and feed emotions, create complacent fictions and blind spots, misuse the great words, and uphold empty slogans.” People “get their picture of one another through the press. The press can be inflammatory, sensational, and irresponsible. If it is, it and its freedom will go down in the universal catastrophe.”

In another, almost-prophetic passage, the report said: “If modern society requires great agencies of mass communication, if these concentrations become so powerful that they are a threat to democracy, if democracy cannot solve the problem simply by breaking them up—then those agencies must control themselves or be controlled by government. If they are controlled by government, we lose our chief safeguard against totalitarianism—and at the same time take a long step toward it.”

Published just after World War II, the report predated the dominance of the press through television, the internet, and podcasts. Except independent media, which often broadcast through podcasts, those who control the corporate press would do well to heed the advice of Robert Hutchins, the commission’s chairman, in the foreword to the report:

“The tremendous influence of the modern press makes it imperative that the great agencies of mass communication show hospitality to ideas which their owners do not share. Otherwise, these ideas will not have a fair chance.”

I side with Taibbi, Fang, and Bongino. Like the voters in the Rasmussen poll, I’m troubled by the swelling of the leftist police state. Among its favorite tools are social-media censorship, indoctrination in many K-12 schools, colleges, and universities, hijacking the English language (malinformation, anyone?), and targeting political opponents—all touted as necessary to preserve democracy. It’s nothing more than Marxism, rebranded for America. Marxism and a growing police state—we must not allow these to be the legacies of 9/11. Nor should we let them strangle our country.

As Bongino rightly said, those who died on 9/11 lost their lives because the hijackers wanted to destroy the liberty and freedom Americans enjoy. We must retell the story of that day and its legacies, both intended and unintended.

I’ve shared my 9/11 story with my children. They know what it was like to be in Washington that day. They know that I went to Ground Zero later to report on a college across the street from the Twin Towers. We watch documentaries on the anniversary of the attacks, and they empathize with the overwhelming sadness of people who lost relatives and friends. I don’t want my children to think America, with its rich heritage of liberty and freedom, has come easily.

On September 12, 2001, America coalesced. We were devastated, but we wouldn’t be defeated. What some men meant for evil, we would use for good. This is the 9/12 mindset we reflect on, an intended legacy we must preserve.

Perhaps the most sterling legacy is that of the firefighters. They battled into the fires that eventually consumed many of them. Why? For the same reasons the young men on D-Day darted into enemy fire on the beaches of Normandy, France. As the classicist and historian Victor Davis Hanson explained in a piece commemorating the 79th anniversary of the invasion:

“How and why did the Americans on Omaha charge right off their landing craft into a hail of German machine gun and artillery fire, despite being mowed down in droves? In a word, they ‘believed’ in the United States.

“That generation had emerged from the crushing poverty of the Great Depression to face the reality that the Axis powers wanted to destroy their civilization and their country. They were confident in American know-how. They were convinced they were fighting for the right cause.

“They were not awed by traveling thousands of miles from home to face German technological wizardry, veterans with years of battle experience, and a ruthless martial code. The men at Omaha did not believe America had to be perfect to be good—just far better than the alternative.”

The first responders on 9/11 no doubt sensed—if they didn’t know outright—that they were fighting a terrorist attack. They were no different from the men on Omaha Beach, which saw the most loss of life on D-Day.

Today, we face an ideological attack that’s no less dangerous to the fabric of our republic. May we adopt the 9/12 approach and the firefighters’ courage as we strive to save and restore the United States.

Leave a Reply