My paternal grandmother was a young girl when she and her parents fled war-torn Greece for the United States. Beleaguered by the constant fighting between the Greeks and the Turks, they had seen family and friends slaughtered. America promised safety and shelter.

My great-grandfather, Gus, landed in America first, around 1917. He had twenty-five dollars to his name—enough for immigration expenses. He would find work and send money home to family members. A few months later, my grandmother, Ann, followed with her mother, Olga.

At left: My great-grandfather, Gus, and my great-grandmother, Olga. An unknown gentleman, seated, cradles my yiayia, Ann. The couple at right is unknown to me. The picture is undated, but it likely was taken shortly after my family arrived in the United States.

Coming to America wasn’t their first choice. They adored their homeland. They struggled, as all immigrants do, to adapt to American culture. They prayed that the climate in Greece would stabilize, and hoped to return. They didn’t plan to stay in the States.

But they did. Ann was the eldest of seven children. One of her sisters died at twenty-six, from pneumonia. One of her brothers died as an infant. Ann and her four remaining siblings went on to have many children and grandchildren. More than a century later, Olga and Gus’s bravery and persistence continue to bear fruit.

My dad and I, along with our aunts, uncles, and cousins, have served America well—as policemen, entrepreneurs, pastors, professional soccer players, members of the armed forces, business executives, doctors, writers, and automotive experts, to name a few. My big Greek-American family overflows with laughter, joy, and warmth. Their work ethic is unparalleled. Their appreciation of good food and their culinary skills are unmatched.

A Love Less Arranged

Greek culture isn’t flawless. We have a nationalistic pride that can be overwhelming. All roads lead to Athens, we often say, with a nod to antiquity and its golden grip on us.

Some of our cultural norms have proved stifling. Arranged marriage, for example. Olga and Gus arranged a marriage for Ann when she was 18. Her opinion didn’t count. She was forced to marry my grandfather, Nick, who was 31.

As part of the arrangement, Nick promised to pay for her to attend college. Ann spoke several languages and excelled in school. She craved higher education. But Nick never delivered on his promise. As one of my cousins explained,

“Had your yiayia gone to school, she could’ve been anything she set her mind to becoming. She was a strong-willed lady. You didn’t want to argue with her, because she didn’t argue about something she hadn’t already studied. She was probably born before her time.”

My yiayia had two children by the time she was in her early twenties. Her dreams dashed, she hardened. My dad spoke of her as icy and stoic—far from a warm mother who lavished him with love. When he was growing up, Ann and Nick didn’t seem to believe in hugs or fun.

When my dad was a young adult, my grandfather decided the family should return to Greece. He was the only one who thought it a good idea. My dad, my grandmother, and my dad’s sister balked. “By then, we were Americanized,” my dad said. They stayed in the States. Nick went back to his native Athens, and lived out his life there.

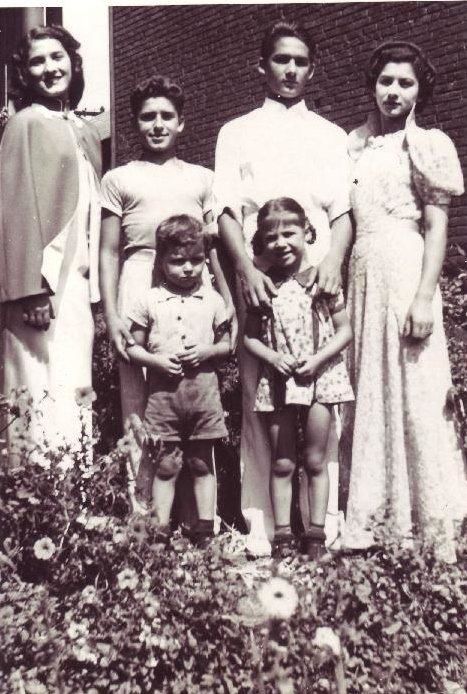

My dad, front-left, and his sister, Daphne, front-right, stand with their aunts and uncles—my yiayia’s younger siblings—circa 1940, in Ohio. At back-left is my great-aunt, Mary, who died of pneumonia at age twenty-six. Her kindness and keen wit are the stuff of family legends.

What If?

About ten years later, my dad married my mom. To Ann’s chagrin, my mom wasn’t Greek. She was German. Given that Hitler had brutalized and starved thousands of Greeks in World War Two, my mom’s heritage didn’t sit well with my grandmother. As a measure of her discontent, Ann moved to California—far from my parents, in Ohio.

Ann visited me just once, when I was a baby. Brief phone conversations with her dotted the landscape of my childhood. “Work and study hard. And go to college before you think about getting married,” she said each time we talked. To my young ears, it was confusing advice. Now that I know her story, it makes sense.

I wonder what would’ve happened if Ann had refused to step into marriage. Maybe she would have gone to college and become a lawyer, an architect, a linguist. Maybe her parents would have disowned her. Maybe she would have forged a relationship with my parents and me. Maybe she would have taught me to speak Greek and regaled me with tales of immigrant life in an America long gone.

I wish I knew Ann as more than a deeply accented, austere voice on the phone. As more than the sharp elegance she showed in photographs. Surely her story was far richer than my experience of her. But how? She is, for me, a mystery.

One day, I pray, I’ll tell her story. Because her life is veiled by the unknown, it would be fiction. There’s joy in that, because fiction grants writers creative licenses for filling in character gaps. I could rewrite Ann—not just into a compelling protagonist, but into the grandmother I wish I had known.

Note: My son’s teacher shared an advent devotional from Biola University that includes the poem below, about immigrant relatives. The devotional and the poem sparked my idea to write this post. I hope you enjoy both. -kc

Prayer for My Immigrant Relatives

By Lory Bedikian

While they wait in long lines, legs shifting,

fingers growing tired of holding handrails,

pages of paperwork, give them patience.

Help them to recall the cobalt Mediterranean

or the green valleys full of vineyards and sheep.

When peoples’ words resemble the buzz

of beehives, help them to hear the music

of home, sung from balconies overflowing

with woven rugs and bundled vegetables.

At night, when the worry beads are held

in one palm and a cigarette lit in the other,

give them the memory of their first step

onto solid land, after much ocean, air and clouds,

remind them of the phone call back home saying,

We arrived. Yes, thank God we made it, we are here.

What an amazing story! I remember being little and going to visit Aunt Ann and Uncle Nick. We had to sit still and not say a word. That was very hard for me being the chatter box that I was. I remember telling my Daddy that I felt sorry for Aunt Ann because she was always so sad. He said she had a hard life. Imagine what she could have done with her life if she had not been forced into an arranged marriage. The sky was the limit with her intelligence.

Thanks, Cindy. I appreciate hearing that she seemed perpetually sad to you as a child. Children know emotions better than adults, in many ways. xo

You have surely filled in some family gaps for me. I will be sure to share it with John and Jimmy. I try to keep as much family history as I can, and I will add your story to my collection. I never met your Mom, but I miss the rest who are gone. It is amazing how much life has changed in the past 100 years. BTW, I’m Zara’s daughter-in-law.

Thanks, Cathy. I’m glad this helps round out a bit of our family history. I’d love to hear what John and Jimmy think. I’ll add you to my email list. Happy Christmas, and hope to talk soon.