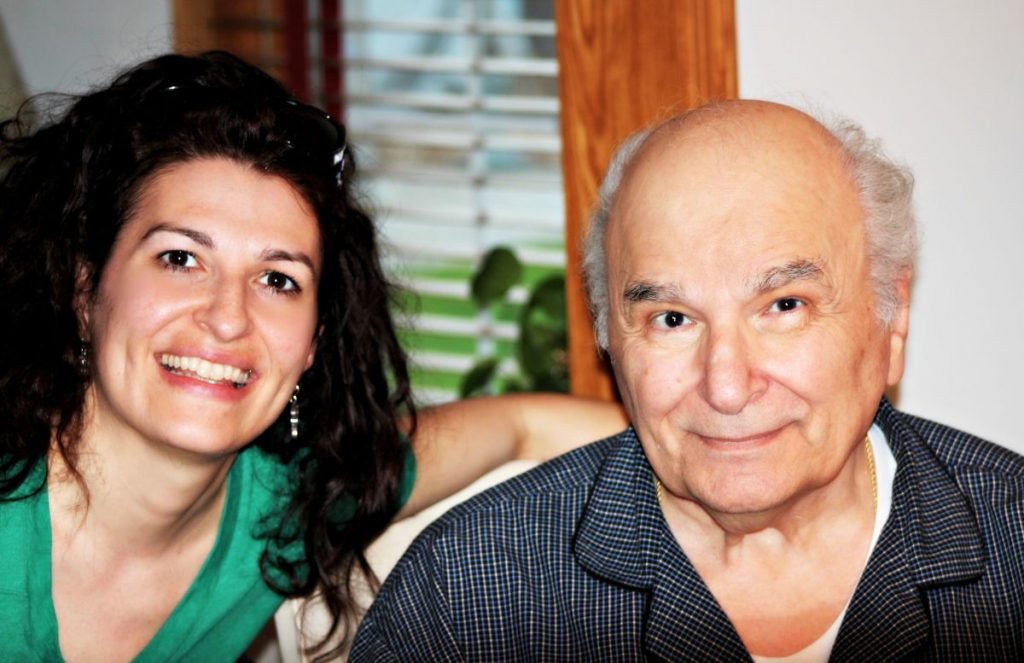

Last summer I lost my dad to heart disease. He was almost 83, and in declining health. He died twice. The first time, he was rescued by a band of courageous Good Samaritans. Their bravery afforded my family and me a chance to say goodbye, and to be with him the second time he died. His last days were nothing short of a miracle. I wrote a narrative essay about them, which I hope will be published in the future.

I would’ve loved to have my dad here for another decade, or longer. His death means I’m an orphan, the dreaded state most of us face sooner or later. But the grief that’s met me in Dad’s wake has been uncomplicated—in many ways, sweet. It’s strange to to see “grief” and “sweet” in the same sentence. I’m used to grief coupled with words like “trauma,” “lifelong,” and “severe.”

As I wrote the essay about my dad, I did cursory research on uncomplicated grief. I couldn’t find anything that spoke to what interested me: After you’ve encountered several complicated losses, how does it feel to experience uncomplicated grief? This is my take.

Complicated Vs. Uncomplicated Grief

I’m no stranger to grief. My family specializes in the complicated kind. We lost my mom to a rare form of breast cancer when she was 46. My brother ended his life when he was 47, after a brief battle with depression and anxiety.

Losing a parent when you’re still a child changes you as nothing else does. It reshapes your world view, restructures your approach to relationships, breaks your heart in ways you spend a lifetime trying to understand. In her book, The Loss That Is Forever: The Lifelong Impact of the Early Death of a Mother or Father, Dr. Maxine Harris writes:

The death of a parent in childhood does not merely mark time for a survivor, becoming one of many important life events. It is the psychological Great Divide, separating the world into a permanent “before and after.” Thirty, forty, or fifty years after the death occurred, men and women still refer to the early death of a parent as the defining event of their lives.

Losing a sibling to suicide turns life inside-out. I’ve always considered my brother, my sister, and myself variations on the same theme. We were supposed to grow old together. Jim’s death thwarted that hope and many others. But because I was an adult when he died, I had the advantage of emotional maturity. I better understood the emotions kicked up by his death, and how to confront and cope with them.

As I settled into writing and revising the essay about my dad, I reflected on my past losses. I’m used to complicated, heavy grief. To my surprise, the loss of my dad felt uncomplicated. The grief load was lighter. What made it different?

- No regrets. Since my dad’s death, I haven’t said, “I wish,” I should have,” or “if only.” We shared a lifetime. He saw me graduate high school, college, graduate school; move around the country; get married; have children and begin to raise them. I got to know him well. Aside from my birth, my mom hasn’t been here for any of the defining times in my life. My memories of her have dimmed over thirty years. I never related to her as an adult, never got to know her in the familiar way so many women know their moms.

- It was his time. Two weeks before he had cardiac arrest, my dad called me to share how dire his heart condition was. Against more interventions, he said he was ready to go if God called him home. I believed him. He ran a good race and finished well. He was ready to push into eternity and embrace the promises of Heaven. I’m thankful for his life. I’ve not focused on the brevity of it, or the way he died. With my mom and my brother, I still have trouble understanding why it was their time. They were in the prime of life. Much awaited them. Many people needed them—and still do. Accepting my mom’s death was easier than my brother’s death. Cancer seems a more natural cause of death than suicide. Everything about suicide is unnatural.

- Gratitude was one of my first responses. In the hours just after he passed, I was grateful for all I had gained from my dad’s life. We shared a bond made stronger because he was my dad and mom for thirty years. His death has been a prism, reflecting the upsides of my past losses and grief. For instance, I tend to think of being motherless as a thorn, one that weakens me. Sometimes it does. Looking back on my dad’s life and our connection, I was newly thankful for that thorn. I saw how it forced me to adapt, to develop strengths I never would have if my mom had lived.

Good Grief

Complicated or not, loss and grief are painful. The world teaches us to hide from, avoid, and deny pain. But it remains. If we don’t deal with it, it weakens us. But if we walk through it, we can grow and learn.

Christ was well-acquainted with grief, loss, and pain. We see it throughout the Bible. After he spoke to Mary and Martha, the sisters of a man—Lazarus—who had died, Jesus wept. He wept despite knowing that in a short time, he would bring Lazarus back to life. Jesus had compassion for those who suffer. He wept as he died on the cross, asking why God had forsaken him.

In her book, The Way of Abundance, Ann Voskamp says,

Blessed—lucky—are those who cry. Blessed are those who are sad, who mourn, who feel the loss of what they love—because they will be held by the One who loves them. There is a strange and aching happiness only the hurting know—for they shall be held.

I’ve never felt closer to God than when I’ve faced a loss, or experienced grief. This was truest when I had postpartum depression, a deep and unique form of grief. Though I hadn’t lost anyone–in fact, I’d gained a new life—I grieved the loss of my old life. I grieved for my mom, who died twenty years before my first child arrived. I promised God that if he brought me through my postpartum grief, I’d use it for good. That good turned into my first book.

When we allow losses and grief to strengthen us, we find comfort and healing. When we take that strength and use it to encourage and comfort others, we become something this world desperately needs: points of grace.

Thank you, Kristina. This is beautiful. There is so much about grief that’s fluid and unknown until we are there. It’s definition is as varied as those who grieve. I’m also no stranger to it & thought I had it figured out. I recently lost my mom. So much of it was sweet as it was time & most of my grieving took place before she passed. Part of my grief was for what we didn’t have in our relationship. Thank you for your strength in using your pain for good:)

My condolences on the loss of your mom, Robin. Thank you for sharing. Well-said about grief. We don’t know what it’ll feel like until we’re in the midst of it. May you continue to know the healing power of Christ as you move through these days and weeks.

Thank you for your beautiful and eloquent post on grief, complicated and uncomplicated. I am left changed and full of introspection. Thank you, Kristina.

That’s gratifying, Julie–thank you. If just one person is enriched, changed, helped by my writing, then I’ve done my job.

Kris this is just beautiful. I felt the same kind of uncomplicated grief this summer when my YiaYia died at 98 yrs old. May all the memories of all of our loved ones in eternal sleep be forever eternal. Love you my sweet friend! ❤️😘

Thank you, Angela, for sharing. As my Nouna says, she thinks of all those who’ve gone before as having a party in Heaven. There’s some grace in that, thinking of the wide embrace that awaits us once it’s our time. Your Yia’s spirit lives on in you, here, just as you know she goes on herself, in the eternal realm that we don’t yet see, but know is there. Love you!