It’s been almost a decade since I left the East Coast. Mostly, I don’t miss it. That is, until I fall back into the rhythm unique to the corridor between D.C. and Boston. I had a chance to do that on a recent trip to Philadelphia, to promote my first book.

I’d almost forgotten how the heat of summer here crawls over you like fast-growing moss, how it saps your energy and patience. I quickly remembered how the high-intensity edge of the place draws me in.

With East Coast cities, many things are the same—and different.

They’re loud, fast, and thick with people.

There’s an immediacy to life. Down time and personal space are relative terms. There are at least 100 things you could be doing, and 50 that you should be doing.

People are kind enough, not overly friendly—not in the way of the Midwest, where grocery cashiers strike up small talk. I lived in and around Washington for almost eight years, and I moved four times. The only spot where I knew my neighbors was when I lived in a dorm.

The cost of living is high. If you don’t work from home, you likely spend far more time at the office—and getting to and from it—than where you live.

Annoyances abound. But for those who love life in the East, they’re worth tolerating, and sometimes, they’re an elixir. I used to be one of them. My time in Philadelphia reminded me that I still am.

You Take the Good, You Take the Bad

Walking is a way of life. Public transportation is easy, cheap, and convenient. Half of the fun lies in getting from one place to the next, on a bus or a train, surrounded by a crush of strangers.

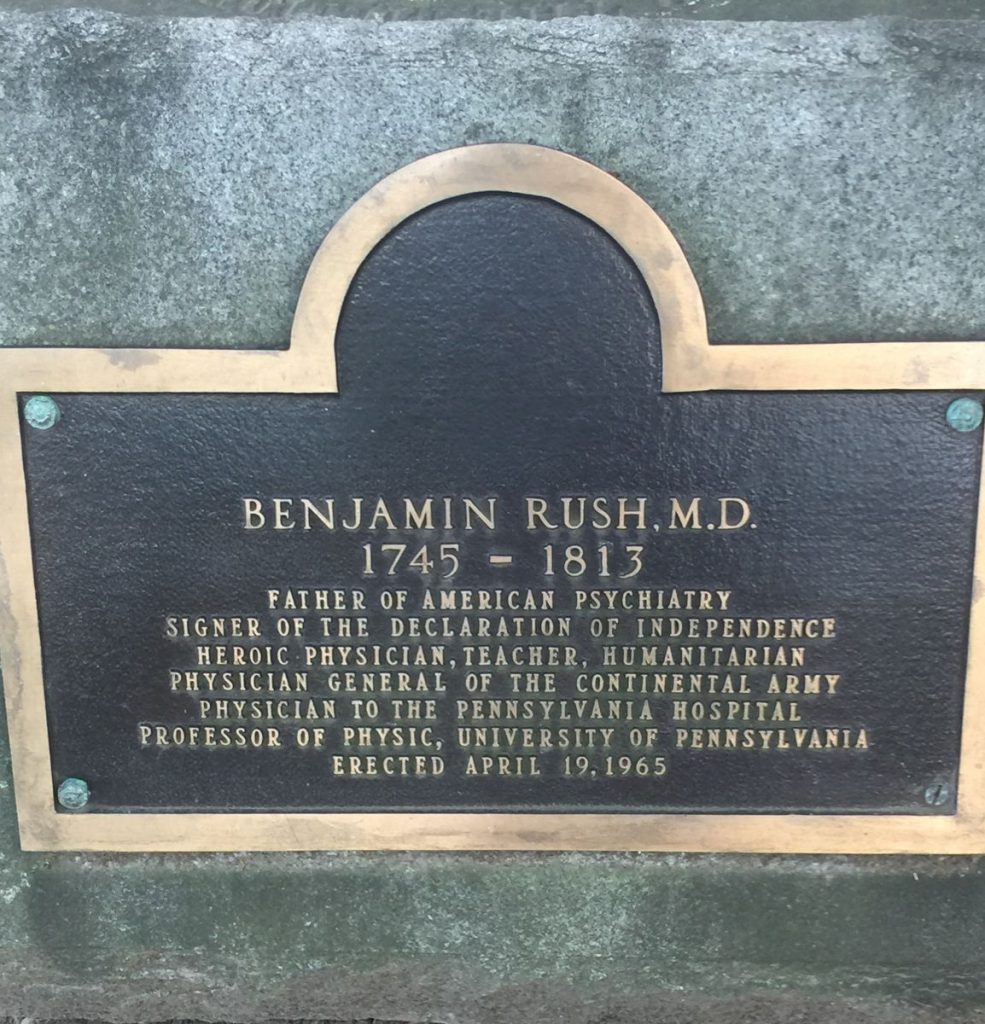

History is the fabric of the East. America’s founders set up shop here, debating what “we the people” should mean. Some are buried here. In the 295-year-old Christ Church Burial Ground in Philadelphia, gravestones are worn smooth, some into small, withered plates of stone barely peeking above ground. Five signers of the Declaration of Independence rest here, including Benjamin Franklin and his family, and Dr. Benjamin Rush. Called “the father of American psychiatry,” Rush was the first to believe that those with mental illness had a disease affecting their minds, and weren’t possessed by demons, according to Penn Medicine’s website.

Christ Church Burial Ground has 1,400 grave markers. Because of erosion, it’s believed that more than 5,000 markers have vanished.

Christ Church Burial Ground has 1,400 grave markers. Because of erosion, it’s believed that more than 5,000 markers have vanished.

Here lies Benjamin Franklin. His grave is visible from the street, thanks to a fence, and passersby often toss pennies as a sign of respect.

Here lies Benjamin Franklin. His grave is visible from the street, thanks to a fence, and passersby often toss pennies as a sign of respect.

It’s fitting that while on a journey to advance awareness for maternal mental health, I encountered the grave of the man who first pulled mental illness from the fringes, into the realm of collective understanding.

It’s fitting that while on a journey to advance awareness for maternal mental health, I encountered the grave of the man who first pulled mental illness from the fringes, into the realm of collective understanding.

I visited the cemetery and Christ Church itself. A church shopkeeper shared this with me: “Benjamin Rush is really the father of modern medicine. As far as this city goes, he should be ranked the second most important man, after Franklin. I don’t think any other city in America has such an odd love affair with one human being [Franklin]. And I don’t think it’s necessarily good.”

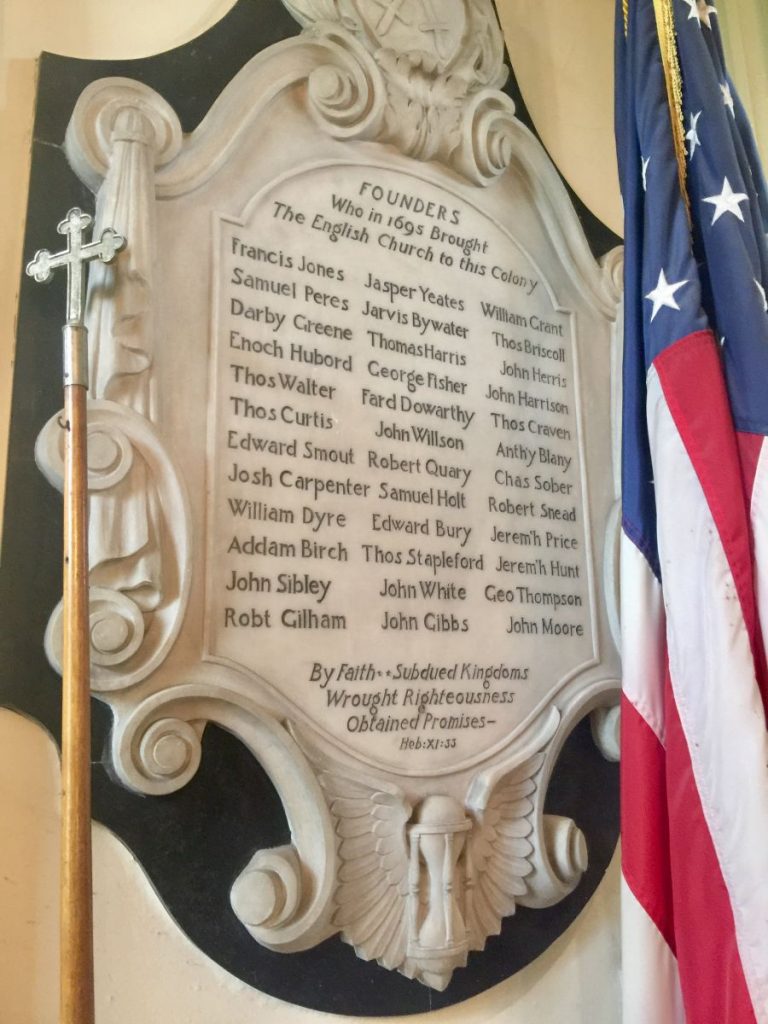

The church was founded in 1695, and the current building was constructed in 1744.

The church was founded in 1695, and the current building was constructed in 1744.

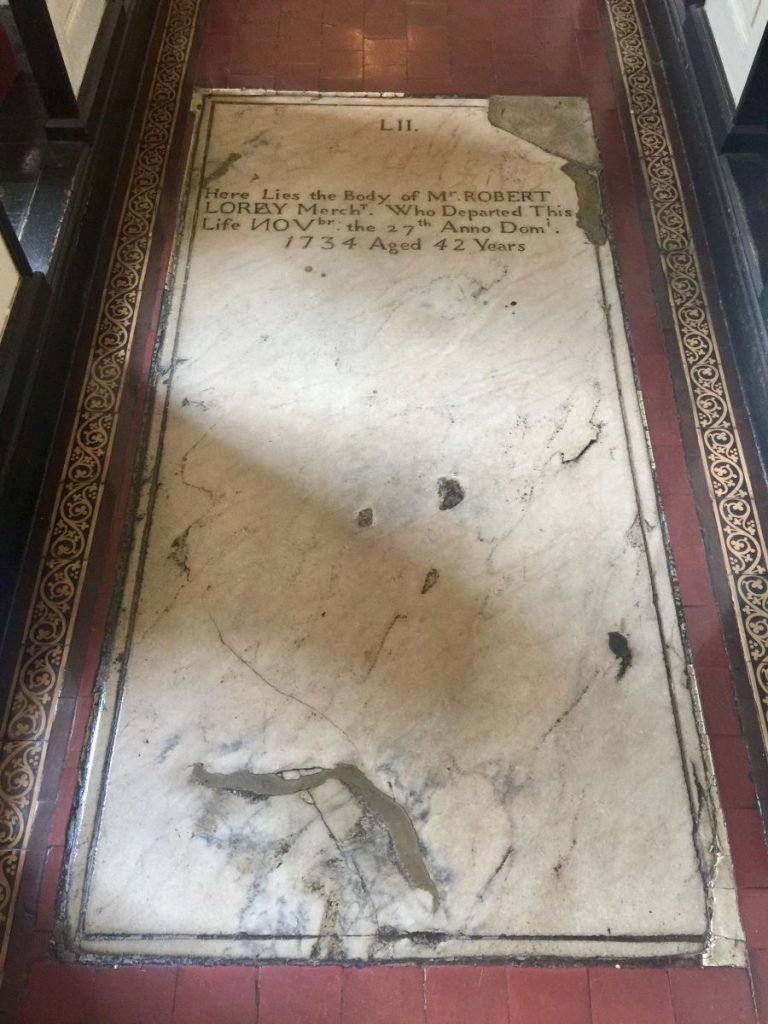

Some are buried inside the church, and the inscriptions, according to a guide, are original. That’s old, for America.

Some are buried inside the church, and the inscriptions, according to a guide, are original. That’s old, for America.

I value Philly’s awareness of history, and dedication to it.

When I first moved to D.C., I felt as if I were getting another degree. I was schooled in Washington logic just by listening to others discuss history, much of it political. Working and living in the capital was one of the best things I’ve done. I’m glad I did most of it when I was single, and my career was the center of my life. In D.C., you are who you know, and what you do. Status is identity. It brings you closer to changing and ruling the world—or at least it makes you think you are.

Even transportation feels political. If you’re on the left side of a moving walkway, you’d better be moving, fast. Otherwise, you risk being trampled. When I first arrived from Chicago, I thought the informal policy was rude, along with the habit of calling the land between the East and West coasts “flyover country.” After I’d lived there for a few years, I was an impatient Washingtonian who shoved past tourists. But I didn’t refer to any part of America as a flyover region.

D.C. wore down some of my Midwestern approach to life. It was the threat of that mindset disappearing that fed my desire to return to Chicago, just before we started a family. I’ll never regret our move.

Likewise, I’m thankful I spent the better part of a decade out East, working more than I should have, running a perpetual career race with the other 20- and 30somethings.

The Joy of the East

I spent three days in Philadelphia, and it felt like home. It left me craving the frequent work trips I used to make. Although I missed my family, I relished the anonymity of being alone in a big city—no meals to make, no errands to run, no sticky faces to wipe.

I enjoyed melting into the masses. I struck the same urgent steps as locals, rushing from one place to the next. I rode the city bus down Chestnut Street. I roamed the streets of the Historic District that honor our founding fathers, and I read about their strengths and weaknesses. They made their share of mistakes. As a result, generations since have faced struggles, but we’ve also reaped plenty of gains. Our first leaders hatched a brave experiment, and it turned out to be the world’s greatest democracy.

I’m grateful that when my Greek grandparents fled persecution in Europe, they landed here. Because of their move, and because of America’s revolutionary thinkers and fighters, my family has known the freedom of life in the United States.

Leave a Reply