Earlier this month I finished my second Avon Walk in Chicago, pounding 39.3 miles of pavement against breast cancer. We were a largely female troop of 2,200, including 276 breast-cancer survivors. Men weren’t absent, though: 329 of them joined our ranks.

Together we raised $4.7 million to help snuff out breast cancer. As a sign along the walking path suggested, we might not see a cure soon, maybe not even in our lifetimes, but one day we’ll extinguish it.

We can’t afford not to care.

Among women in the United States it’s the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the second leading cause of death. More than 250,000 women under the age of 40 are living with it. The World Health Organization says breast cancer is the most common cancer among women worldwide, as well, killing hundreds of thousands every year in countries at all levels of modernization.

I signed my Mom’s name atop the Chicago portion of an inflatable pink tower that travels to all Avon Walk cities. Photo by Kristina Cowan

Breast Cancer Doesn’t Discriminate

In the weeks leading up to the walk I learned of two young moms who lost their lives to it. One was a friend’s friend, a woman named Dana who left behind a loving husband and two small children. When I was buying gear for the walk, I heard the story of another. The woman ringing me up related how her sister had just died from breast cancer. She ached for her motherless nephews.

Breast cancer attacks wherever, whenever, whomever. It ravages us in our prime, when we’re launching our careers, when we have young families who desperately need us.

A speaker at the walk’s opening session was 33-year-old Trish Russo, a three-time breast cancer survivor. At 30 she learned she had an aggressive form of breast cancer. It had spread to her brain, but so far she’s beating it. Another speaker cried as she explained recently losing her daughter who also was her best friend.

At 45 my Mom learned she had a rare, inoperable form of the disease. Doctors treated her with chemotherapy first, and radiation when it started spreading. A year-and-a-half later the staff at University Hospitals of Cleveland said there was nothing more they could do. She was dead at 46.

That was 25 years ago, when the disease peaked in the United States at a rate of 33 deaths for every 100,000 women. Since then the breast-cancer death rate has been declining steadily. The latest data available are for 2007, when the U.S. mortality rate was about 23 deaths for every 100,000 women.

The National Breast Cancer Foundation attributes the declining death rates partly to better screening, early detection, increased awareness, and continually improving treatment options.

In my Mom’s case, early detection could’ve saved her life. She lived with a lump in her breast for a year before she sought help. Once she went for tests the mass was easily the size of a tennis ball. Taking a cue from her inaction, I started getting mammograms at age 29.

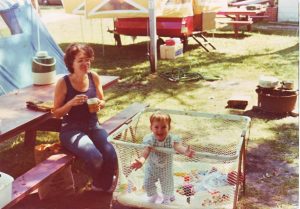

My Mom and me sometime in 1975, camping in our native Ohio. I’d like to outlive her 46 years.

Photo by Dean Lane

Several women I know have benefited from early detection, including my godmother, and today they lead healthy, full lives. To look at them is not to know cancer ever plagued them.

Cancer and Stress

Finding a cure for breast cancer means understanding what causes it. Diet, exercise, bad habits, genetic predisposition–all of these come to mind. In my Mom’s case diet probably played a part. She was known to drink at least a full pot of coffee every day, and eat decadent foods.

More important than these was the role of stress in her life. She grew up with an alcoholic father, was abandoned by her first husband who left her with my two then-small siblings, suffered a brutal attack and rape in her early 20s, and later confronted with a senseless divorce from my Dad. Tragedy was her constant companion, one I believe led to her physical demise.

Early nineteenth century physicians such as Nunn emphasized that emotional factors influenced the growth of tumors of the breast, and Stern noted that cancer of the cervix in women was more common in sensitive and frustrated individuals. Walshe’s major treatise The Nature and Treatment of Cancer called attention to the “influence of mental misery, sudden reverses of fortune and habitual gloomings of the temper on the disposition of carcinomatous matter. If systematic writers can be credited, these constitute the most powerful cause of the disease.” One hundred years ago, Snow’s review of over 250 patients at the London Cancer Hospital concluded that “the loss of a near relative was an important factor in the development of cancer of the breast and uterus.”

I attach particular importance to these observations, particularly the last, because the practice of medicine one or two hundred years ago was much more personalized. Physicians had to rely more upon their own understanding of the significance of the history, emotional background, and life‑style of the patient, in contrast to today’s emphasis on detached diagnostic high tech laboratory and imaging procedures. In addition, their education was more apt to include a heavy background in literature, the humanities, and philosophy, rather than the current accent on basic science. They were much more likely to be familiar with the patient’s family and social relationships, and the influences of other psychosocial environmental factors.

The loss of an important emotional relationship is a major factor to consider in cancer, Rosch says, particularly the loss of a spouse through death or divorce.

Stress is difficult to measure, and modern medicine doesn’t seem to give it too much thought. It’s difficult to manage, too. Losing a spouse, for example, is a major source of stress beyond our control. Yet we can control our internal response to it, and build a healthy emotional base of friends and family.

We can do the other things, too, like eating well and exercising. We might even choose to walk 40 miles one weekend every year, around a prime spot like Chicago. Events like the Avon Walk might pose temporary physical stress, but they do our minds good in the long term, reminding us that we’re not powerless in the fight against cancer.

Leave a Reply